A Few Thoughts on A Complete Unknown

While we were in Utrecht for the Jack White show, the lovely M and I found the time to swing by a big, fancy Dutch movie theater to see A Complete Unknown, which has been around for a while in the States but just came out in Europe last week. I have to admit that I had been pretty eagerly anticipating this one. Music biopics are, in general, a bit of a guilty pleasure for me, but this one in particular covers a story and a body of work that I’ve been interested in for the vast majority of my life. It’s also apparently partly based on Dylan Goes Electric, a fantastic book by Elijah Wald, who is possibly my all-time favorite music writer and someone who I regard as a mentor.

I went in fully expecting my mock outrage at small historical inaccuracies to be a big part of the fun, and it was. This kind of hole poking nearly always plays a role in my enjoyment of movies like this, unless, like certain movies about the beatified lead singers of legendary English rock bands, they take indifference to history so far that it becomes difficult to enjoy. Even compared to some of my other favorite music biopics, like Ray, Amadeus, and The Dirt, though, this one covers territory that I’ve spent a lot of time learning about, so I came prepared. A lot of the little holes I found to poke were inoffensive or even justifiable in the name of narrative efficiency.

For example, I can see why they chose to have Joan Baez perform before her first encounter with Dylan at Gerde’s Folk City, a venue that would have been pretty far below her pay grade at the time. I can also see why they changed the song Pete Seeger wanted to play for the judge at his March 1961 trial from “Wasn’t That a Time” to the much more familiar “This Land Is Your Land,” and why they decided to place Pete in the hospital room when Dylan first comes to visit Woody Guthrie, even if it is a bit sad to cut the person who probably really would have been there, Woody’s ex-wife Marjorie Mazia, who had been the principle dancer for the Martha Graham Company, and who not only cared for her ex until he finally died in 1967 but went on campaigning against the disease that killed him for the rest of her life. These changes, by and large, serve to tighten up the story without doing that much harm, and if they give nerds like me something to bitch about, all the better. There were, though, a few liberties taken by the makers of this movie that trouble me a bit more.

Woody Guthrie and Marjorie Mazia

Why, for example, would they have Dylan sitting on the sofa in Pete and Toshi Seeger’s log cabin playing “Girl from the North Country,” right after his arrival in NYC at the beginning of 1961, when that particular song, being largely based on English folksinger Martin Carthy’s version of “Scarborough Fair,” which Dylan learned during his first trip to England in 1962, is one of the easiest Dylan compositions to trace in terms of compositional timeline? The fact that they had Dylan writing the song a year or so too early doesn’t bother me, but it strikes me that having him writing it before he ever heard the song he based it on does damage to the story that they’re trying to tell with this movie, which is, as I see it, the story of Dylan’s spectacular entry into and then gradual disillusionment with and drift away from the priorities, ideologies, and agendas of the New York folk scene.

In another scene a bit later in the movie, Dylan is in the studio playing “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” during the sessions for his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Watching from the booth, a clearly impressed Tom Wilson, who produced a run of albums for Dylan before going on to work with The Velvet Underground, The Mothers of Invention, and others, is sitting in the booth with Albert Grossman, Dylans manager and the man who, for better or worse, did more than anyone else to turn the folk revival into big business. Wilson, clearly impressed, asks “Who wrote this?” In reply, Grossman simply points at Dylan.

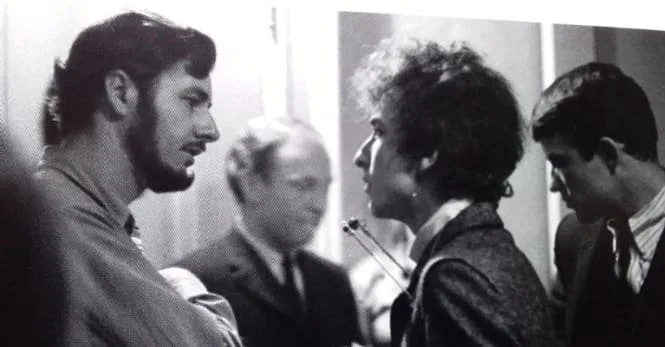

Paul Clayton chatting with Dylan backstage at Carnegie Hall

Well, yeah,… Kinda. But here’s the thing. At the time when Dylan came to New York, one of the prime movers in the Greenwich Village Folk Scene was an eccentric folk singer with a buttery, Leonard Cohen-esque voice named Paul Clayton. Clayton had a cabin in the little town of Brown’s Cove, Virginia, which he used as a home base when collecting folk songs from people who lived nearby. There, in the late 1950s, recorded a woman named Mary Bird Bruce McAllister singing a song called “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone?” He then recorded his own version in 1960, with the lyrics modified, for some reason, to “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons….” Dylan then heard Clayton’s song, took a few lyrics and snippets of melody from it, and then used them as a framework to build “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.”

There can really be no question about this influence. Dylan knew Clayton pretty well, well enough to have celebrated his twenty-first birthday in the Brown’s Cove cabin, and, at least according to several witnesses, he specifically commented on how much he liked Clayton’s recording of the song. None of this is really to question the provenance of these songs. Both “The Girl From the North Country” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” are certainly written by Bob Dylan, and in my opinion, both are vastly superior to the songs he based them on. It is, however, an illustration of the way he operated during his transition from interpreter of traditional songs to singer songwriter, and it’s not at all limited to these two examples. The more you listen to roots music from the 1920s and 30s and to other urban folk musicians from the 50s and 60s, the more you notice the seeds of Dylans songs. Sometimes he took more and sometimes less, but something is there to be found in an astonishing number of his songs.

The Carter Family

This approach totally makes sense when you consider that Dylan’s primary early influence as a songwriter was Woody Guthrie, whose songs were nearly always re-texted versions of pre-existing songs (“This Land Is Your Land,” for example, is based on “When the World’s on Fire” by the Carter Family). To Guthrie’s original audience, this would have been totally obvious, because he tended to choose relatively recent hits or songs people had grown up singing in church. We just don’t hear it now, because his songs have often outlasted their sources. Dylan, on the other hand, tended to choose songs that were, at least outside of the folk scene, a bit more obscure. Over time the range of his sources expanded in many directions — his breakup song with the folk movement, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” was similarly inspired by an early rock ’n’ roll song by Gene Vincent — but his tendency to start from a seed of something else continued well beyond the period covered in this movie, and may still not really have completely gone away.

He also maintained more of a connection with traditional music than he may have been eager to advertise after his rockward shift in the mid sixties. Towards the end of the movie, when he and his electrified band begin their set at the 1965 Newport Folk festival with “Maggie’s Farm,” a song that may have been intended specifically as a dig at Pete Seeger, Alan Lomax comments that “you’d might as well just throw a dime in a jukebox,” indicating that he sees little difference between what Dylan was doing and run-of-the-mill teen pop music. Lomax may well have said that. He was certainly very concerned about the seeping of commercialism into the festival, and he was on a particular tear after his confrontation with Albert Grossman (more or less accurately depicted in the movie) the day before.

Alan Lomax, looking fed up

It does strike me as just a bit odd, though. In part this is because Lomax, who was far more willing than Seeger to accept rock ’n’ roll and other electrified music as legitimate folklore, wouldn’t have been likely to reject music because it featured a heavy electric guitar. But then he was also extremely suspicious of middle class kids trying to wedge their way into proletarian traditions, so Dylan might not have been all that likely to benefit from this open-mindedness. More significant is that fact that Lomax, along with a whole lot of other people in the audience, would have recognized the song as a variation on “Down On Penny’s Farm,” by the Bently Boys, one of the most popular standards from Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, the first great compilation album, which was treated like the Bible in many segments of the folk revival.

(Right to left) Dave Van Ronk, Bob Dylan, Teri Thal (Dylan’s first NYC manager, married to Van Ronk), Suze Rotolo, Unknown friend (could be singer Karen Dalton, in memory of whom The Band wrote the song “Katie’s Been Gone”

So, why did Bob Dylan come to New York in the first place? The movie makes it pretty clear that he came to visit Woody Guthrie in the hospital, and there is definitely some truth to that. He did visit Guthrie within the first week of his arrival in the city, and many more times after. Dylan seems to have liked to emphasize this, perhaps because his relationship with Guthrie was something that made him stand out among his generation, but it may not really have been his primary reason for coming.

Greenwich Village was the home of a folk music scene that had already been growing and developing for more than twenty years when Bob Dylan first came through the Lincoln Tunnel. This was a folk music scene, not in the modern sense of singer songwriters who play acoustic guitars (a concept which Dylan probably did more than anyone else to help create) but in the older sense of musicians who were primarily interested in interpreting pre-existing songs from folk traditions for modern audiences. He may have been keen to downplay this later, but at one time Dylan was incredibly eager to be a part of that world. When he almost immediately took that scene by storm, and for most of the years that he spent as one of its primary figures, it was as an astonishingly vibrant and charismatic interpreter of traditional songs.

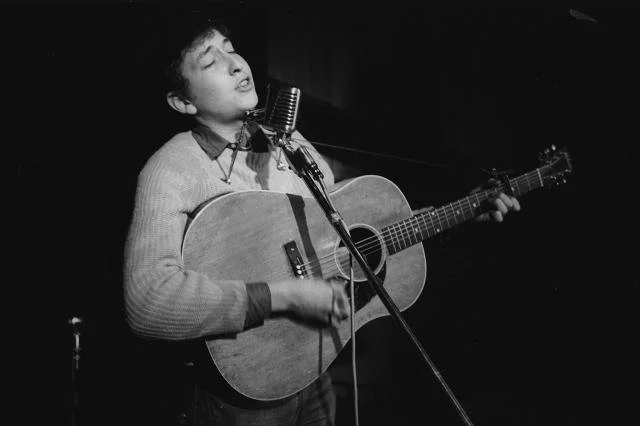

Young Bob Dylan, almost certainly playing something he didn’t write, and he seems pretty into it.

There’s strikingly little indication that such a scene ever existed in A Complete Unknown. We see a few of it’s iconic spaces, such as Gerde’s Folk City, The Gaslight Cafe, Izzy Young’s Folklore Center and maybe the Cafe Wha?, the tourist trap where Dylan first performed when he came to town. However, other than a brief pan over a few guys in a bar, one of whom looks suspiciously like Dave Van Ronk, engaged in an inane discussion about whether a particular artist (I can’t remember who) should be regarded as country of folk, the movie features almost no sign that the neighborhood contained other musicians his own age for him to befriend, be influenced by, and compete with. The only exceptions are Joan Baez, who came from the Boston scene and, anyway, was already a big star when the movie begins, and Bob Neuwirth, Dylan’s long-time friend and road manager. Dylan and Neuwirth actually met in 1961, shortly after the former’s arrival in New York, and this might have made a nice bit of early human contact for him in the movie, but here it’s implied that they only met in 1965, by which time, as we see nicely expressed in a long shot of a black-clad Dylan walking aloofly down MacDougal Street, he was still living in the village but had little to no connection to the scene.

Downplaying this aspect of his early career seems to have been a part of Dylan’s agenda ever since he started to reach wider audiences with the topical songs that he published in a mimeographed magazine called Broadside, beginning with “Talking John Birch” in February, 1962. In part, this might have been due to the disappointing reception of his first album, released the following month. This was the culmination of the project he’d been engaged in up to that point, and the apparent lack of interest in it may have convinced him that he needed to find a new direction.

It’s also worth remembering that the initial recognition he received, outside of the small pond of New York folk fans, was primarily through versions of his songs by other, more accessible artists like Baez, Judy Collins, Peter, Paul, and Mary, Pete Seeger, and, later, The Byrds. This was a huge deal for him, so it very likely seemed to be in his best interests to present himself primarily as a songwriter, and, for the most part, that’s the story he’s stuck to ever since.

A Complete Unknown, unlike the book it’s apparently based on, tows the line of this narrative deferentially. The first song we hear Chalamet’s Dylan sing, for Woody Guthrie in the hospital, is his “Song to Woody,” it’s melody swiped from Guthrie’s own “1913 Massacre,” (a song Dylan also performed) which is itself loosely based on an English balled called “To Hear The Nightingale Sing.” From that point on, there’s absolutely nothing in the film to indicate that Dylan ever had any interest in being anything other than a singer-songwriter.

The only thing that could be called a folk song that we ever hear him play is a tiny snippet of Booker T. Washington “Bukka” White’s “Fixin’ to Die” while in the studio recording his first album, and this is just an excuse for Grossman, who didn’t actually become Dylans manager until about six months later, to suggest to producer John Hammond, that they try out some of Dylan’s own material. Hammond, maybe the most legendary talent scout of all time, who had pretty much jump started the folk revival with his From Spirituals to Swing concerts in 1938 and ’39, is relegated to the role of the stodgy philistine and pooh-poohs the idea, insisting that they stick to traditional material.

Pete Seeger (Edward Norton) gives Bob Dylan (Timothée Chalamet) a look

This exchange is altogether typical of this movie, in which the folk scene is primarily depicted as a cabal of old men (some of them younger than I am now) including Alan Lomax, Theodor Bikel, Harold Leventhal, and of course Pete Seeger. Seeger, who despite any faults he may have had, was never anything if not earnest, is a bit more sympathetically portrayed, despite one “Emperor Palpatine looking at Anakin Skywalker” moment and a very funny reference to the legend of him trying to take an axe to the sound cables at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. The rest seem to have no characterization other than a desire to maintain the status quo, sap Dylan for everything he’s worth, and hold him back from achieving his dreams.

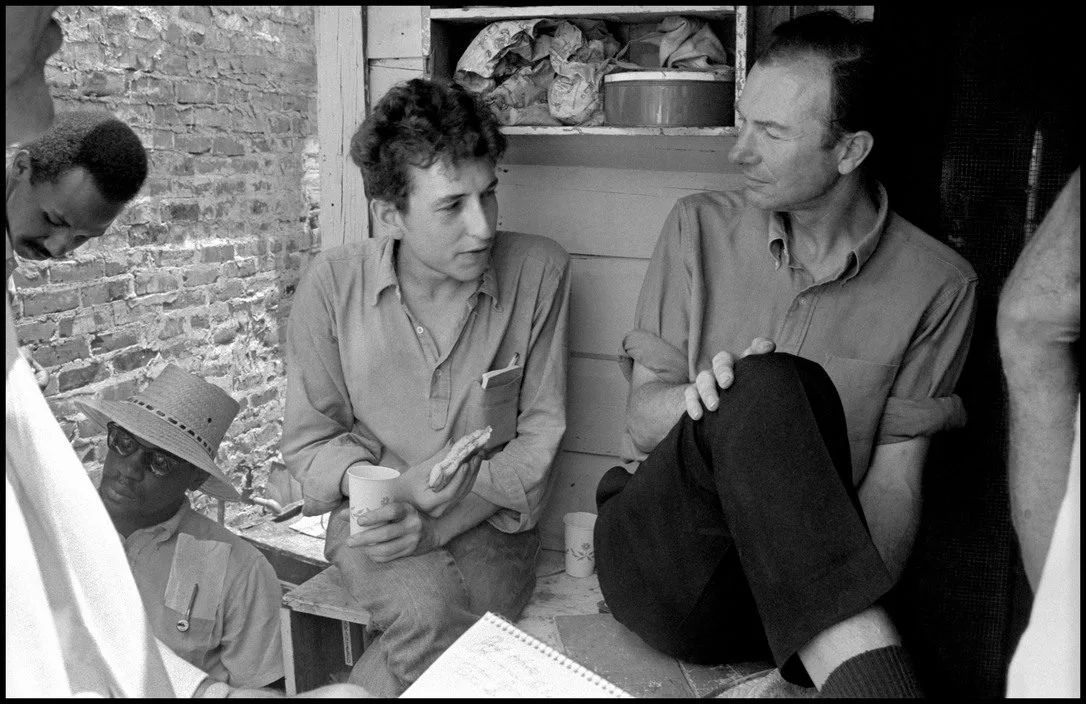

Dylan and Seeger in real life

Again, there is some truth here. There’s a lot to indicate that Seeger and the rest saw in Dylan an opportunity to take their dream of communal music-making for a common and virtuous cause to a new and massive audience and that they were bitterly disappointed by his refusal to play along with their agenda. There is also plentiful evidence in Dylans lyrics that he resented what he saw as exploitation on the part of these scions of the folk movement. But there was, at times anyway, also mutual respect and admiration between Dylan and each of these men.

Dylan hangs out with actual friends at the Kettle of Fish bar on MacDougal Street

There was also a younger, rougher, and wilder segment of the folk revival with aesthetics and ideals that resonated much more deeply with Dylan’s, and it was largely a desire to become a part of this group that brought him to New York in the first place. At least for a while, they became his friends, the people with whom he drank, smoked pot, laughed, spent long nights talking about music, philosophy, politics, relationships, and god knows what else, traded songs and licks, and even sang Elizabethan Madrigals.

Dylan, again with friends, making music with Karen Dalton (this time I’m sure) and Fred Neil

Whatever the makers of A Complete Unknown may want us to believe, for the first two years or so that Dylan was in the Village, he was not only interested in interpreting traditional music, he was spectacular at it. He was the kind of performer who made other musicians who heard him think about quitting, because he was able, seemingly without effort, to attain something that they had been striving for, to a level beyond what they had ever dared to imagine. As Wald writes, “the New Yorkers were learning rural traditions as outsiders and needed to be careful to get them right, but Dylan acted like an insider, someone who had picked up whatever came his way as he wandered around the country.”

Like anyone, but perhaps more than anyone else, Bob Dylan has always operated in phases. Even during the period covered by the movie he went through at least three different major shifts in his aesthetic approach, each of which alienated a large segment of his audience and attracted a larger new one to take its place. You can’t really blame him for wanting to emphasize the place where he is at any given time and downplay what came before. Nonetheless, the time Dylan spent as a folk musician, in the older sense of the phrase, was incredibly important to his development as an artist, had a tremendous influence on kind of singer-songwriter that he ultimately became, and continues to have an impact on his songwriting even today. This fact is supremely present, right below the surface, in the songs they chose to include in A Complete Unknown. It might have been nice to see at least a hint of it in the movie.

Things starting to get intense between Barbaro and Chalamet as Baez and Dylan

OK, now I’ve spent way too much time telling you what bothered me about the movie, so I guess I had better end by telling you about what I liked about it. First of all, pretty much all the musical performances in the movie are spectacular, particularly those by Timothy Chalamet, Monica Barbaro, and Edward Norton in the roles of Dylan, Joan Baez, and Pete Seeger. Chalamet can’t sing quite as good as Dylan, but as someone who has spent hundreds of hours trying to play “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” I was incredibly impressed by his work on the guitar. Actually all three of them play their instruments like they’ve been doing it since they were kids. I assume they haven’t, but either way, it’s very impressive, and when I heard that all the performances in the movie were recorded live during shooting, all with period-accurate equipment, I was blown away.

In terms of vocals, a major highlight is when Chalamet and Barbaro sing together, which they do quite a bit in the movie. I actually think their voices might blend a bit better than Dylan’s and Baez’s did in actual reality, and they bring a certain dynamism in a few moments that I’ve never seen in real life footage of the pair. I think we can forgive them for that, and it’s actually helped me to appreciate Baez and Dylan’s real-life duet performances more than I ever had before.

Pete, Toshi, and their kids at their log cabin

Meanwhile, Norton’s performance, while relatively brief, is a spot-on revelation that totally captures Pete Seeger’s combination of self-effacing kindness and at times overbearing idealism. I loved seeing the vibe of him and his family living their self-consciously simple life in the log cabin he and Toshi built with their bear hands, with a chimney made (in part) from rocks that were hurled at them during the Peekskill Massacre. Even more, I loved seeing how they captured Pete’s unique ability to get an audience singing, in a performance of the Weavers classic “Wimoweh” early in the movie. After seeing that, as I said to M, even if the rest of the movie were awful, it would still be worth the ticket price.

I was also impressed, to my surprise, by the depiction of Sylvie Russo, a stand-in for Dylan’s Greenwich Village girlfriend Suze Rotolo (the woman standing with him on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan). I was a big fan of Rotolo’s memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time, which provides a unique perspective, not only on Dylan’s early career, but on a lot of other things that were going on at the time as well, and I was kind of dreading it when I heard that they had replaced her with someone who I feared would be just some generic arm candy.

Bob Dylan and Suze Rotolo

Rotolo played a huge role in introducing Dylan to the world of politics, art, poetry, and city life in general that was extremely important to his artistic and personal development going forward, and she wasn’t about taking shit from anybody, especially him. I felt like they did a pretty decent job of putting that across, thanks largely to an extremely compelling performance by Elle Fanning. Of course there are a few historical inaccuracies in the depiction of their relationship. She didn’t actually come with him to Newport in 1965, but if I had a chance to re-edit the movie, I wouldn’t dream of cutting the scene of them sharing a cigarette through a chainlink fence before she boards the ferry to leave, which was, to me, one of the most touching and human moments in the movie.

All told, I would highly recommend this movie to anyone, especially to anyone who is interested in the history of popular music. It’s clear that I have some issues with the short shrift given to folk music, and I’m still waiting for the movie that will really capture the magical vibe of the folk scene in Greenwich Village during this era, but despite that, this is one of the few music biopics I’ve seen that I can genuinely call a pleasure, with no guilt needed.

-Peter Lawson - 6 March 2025