The Complete Story of Digital Underground’s Sex Packets

Part 1 - They Say That Birds Do It, Bees Do It

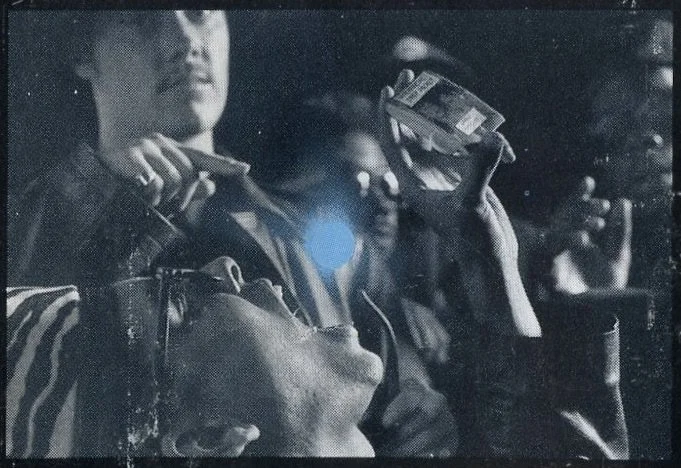

When I was in fifth grade and right on the cusp of puberty, a friend of mine had a couple of cassette tapes that were so precious, so provocative, that he kept them hidden under his mattress. One of them was a cassingle (remember those?) of “Me So Horny,” the biggest hit produced by the much maligned Miami hip hop group, 2 Live Crew, a song that struck me as pretty forgettable then, as it still does now. The other one, though, was something special. Its cover featured a group of six guys, all wearing sunglasses, dark jackets, and astonishingly varied headwear. Five of them look on with respectful gravitas while the sixth, clearly the guy in charge, holds a mysterious blue glowing package about the size of a condom wrapper, which is what we first assumed it to be. Above them is printed a title designed to elicit equal parts titillation and confusion in any eleven year old. This was my first glimpse at Sex Packets, the first and greatest album of the most irreverent crew in hip hop, Digital Underground.

On it was a song that would change my life, “The Freaks of the Industry.” I’ll never forget the first time I heard it, both of us holding our ears close to my hand-me-down yellow Sony “sport” boom box so that we could hear everything without the risk of any sound making its way to my parents’ ears downstairs. The extremely smooth bassline, accompanied by ecstatic moans, neither of which I recognized from Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder’s sexed-up disco classic “Love to Love You Baby,” immediately had me on board. Then, after a brief chorus introducing the two featured M.C.s, Money B and Shock G, as the titular freaks and explaining that anyone who sees them back stage should be prepared to “G”, Money B opened the first verse with the lyrics, “They say that birds do it, bees do it, Time to freak, Money B gets to it…” and I was enthralled. This was exactly the song that my burgeoning interest in sex had been waiting for.

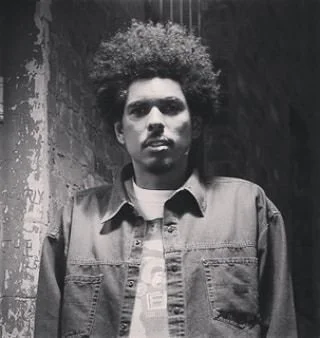

The titular freaks

Looking back now, I’m amazed by how innocent most of the lyrics actually are, with the exception of one reference to anal sex that I can remember being a bit confused by, but at the time I was blown away by the sheer salaciousness of the thing. Bear in mind that not so long before this, having had the basic ins and outs of human sexuality (or at least one small segment of it) explained to me by my dad, I had been utterly shocked by the realization of just what Marvin Gaye was suggesting that his partner wake up for in “Sexual Healing.” Sex still seemed like such a scandalous concept that it was hard to imagine anyone talking openly about actually doing it, much less on adult contemporary radio.

Nonetheless, as soon as I heard “Freaks of the Industry,” I knew that I wanted it in my life. I don’t know quite what I thought of it as a piece of art at that time. I don’t even think I was aware that it was on the same album that also featured “The Humpty Dance,” a song that everyone knew from MTV and the radio. I just wanted it, I suppose, as a symbol of my budding maturity. I got my friend to make me a copy on a blank cassette and proceeded to spend hours listening to it over and over again, learning every word and every inflection until I could, and very likely did, do it in my sleep.

Skip forward a couple of years, and my older sister Sarah, who was and is the cool kind of older sister, would usually let me tag along with her to parties and get-togethers with her older friends where I probably had no business being. Nothing in this world is truly free, though, and in this case the price of admission was very often “Freaks of the Industry.” It turns out that nothing is quite so amusing for drunk 17 year olds as a drunk 14 year old rapping explicitly about sex, so I was asked to do it again and again, and eventually I came to be fairly well-known as the “Freaks of the Industry” kid, something which I assume pretty much ever American high school in the 90s had at least one of.

At some point in all this, after the novelty had worn off, I started to realize just what a strange artifact this song actually was. For one thing, it ended with an extended keyboard solo by someone, referred to simply as the Piano Man, who actually seemed to have a delicate touch and decent jazz chops. To say that this was unusual for a hip-hop song, especially in 1990, would be an extreme understatement, but that wasn’t even the weirdest thing about it. More striking was the way in which it seemed to be presented as a joke but then carried out with complete earnestness and a fair amount of subtlety, and this sort of ambiguity extends to many other aspects of the song. The beat, similarly, is primarily based on the warm, lush world of a Eurodisco slow jam but places it in a hollowed-out, distant context, laced with jittery electronic melodies that give the whole thing a feeling of alienation and suspense.

Meanwhile, the two M.C.s open the song as a swagger-laden exercise in braggadocio about their backstage exploits, but then the encounters they describe seem curiously tender and intimate, and their boasts to one-another are surprisingly focused on their ability to pleasure their apparently random partners. They even end the lyrical portion of the song with a declaration of their eagerness to perform oral sex. When you consider that, just over a year before, Eazy E had opened his debut solo album with a song in which he declared, "I might be a woman beater but I'm not a pussy eater,” you can start to imagine how much stuff like this went against the grain in 1990.

At some point, probably when I was around 16, I got curious enough to buy a copy of the full album on CD, and it soon became apparent that “Freaks of the Industry” was just the tip of the iceberg. On my first listen, I was initially lulled into complacency by “The Humpty Dance”, an extremely weird song, but one which I already knew well, and the two deceptively normal sounding tracks that follow, “The Way We Swing” and “Rhymin’ on the Funk,” which together form a kind of manifesto for the group. I don’t remember what I might have thought of the brief instrumental, “The New Jazz (One)” that follows, but the next song, “Underwater Rimes (Remix)” completely blew my mind. This self-described “underwater hip hop extravaganza” tells a story set in a fully developed fantasy world, complete with a curmudgeonly shark, a turntablist octopus, and a complete verse performed by a rapping blowfish (which, I’m very proud to say, my ten-year-old son can recite from beginning to end). On top of that, it was funny; not a little bit funny, as rappers often are, but really legitimately funny! Even at sixteen I could tell that this was something completely out of the ordinary, and I hadn’t even heard the sci-fi mini-opera that closes the album yet!

Over the years that followed, I became very familiar, some might even say obsessed, with this album, but both it and Digital Underground, the group responsible for it, always remained a bit mysterious for me. Occasionally I would hear things, mostly about the true identity of their most famous character, Humpty Hump, or the group’s connection to legendary rapper Tupac Shakur, but it’s only now, more than thirty years after I first heard “Freaks of the Industry” that I feel like I have somewhat of a handle on who Digital Underground were, how they came together, and how they ended up creating something as uniquely and beautifully absurd as Sex Packets.

Gregory Jacobs (AKA Shock G)

Part 2 - Deep Sea Gangster, Underwater Prankster

There is one primary factor that explains the bizarre but charming uniqueness of Sex Packets, and that is Gregory Jacobs, commonly known as Shock G, the founder and defining figure of Digital Underground, who was, until his untimely death in 2021, one of the most singular and eccentric characters, not just in the history of hip hop, but of all music. Jacobs was born in Brooklyn in 1963, but his family soon moved to Tampa, Florida, where he spent an idyllic childhood, according to him, swimming in rivers and lakes and catching snakes and alligators with his bear hands. He also discovered and fell in love with George Clinton’s theatrical, science fiction influenced funk collective, Parliament and Funkadelic, and from the age of 11 he was playing the drums in local funk groups. Then, when he was in his early teens, his parents split up and he found himself caught between two families that he described as Good Times vs. another show that took place in Brooklyn and featured Malcom Jamal Warner, Phylicia Rashad, Tempestt Bledsoe, Keshia Knight Pulliam, and Lisa Bonet.

His mom, who was more Good Times, took him back to New York, where she would pursue her dream of working in Television. This put him in the right place at the right time to experience hip hop in that magic moment when it had already become a huge cultural phenomenon across the city but hadn’t come to the attention of the commercial music industry yet. He traded his drums for turntables and started rapping under the name MC Starchild, a nod to the hero of George Clinton’s “Funkology,” and writing graffiti as Rackadelic. When a cousin advised him that Starchild was a lame name for a rapper and suggested that he call himself Shah G, Jacobs either misunderstood or thought better of the idea and changed Shah to Shock, which was, according to him, a common hip hop prefix in Queens, where he was living at the time, akin to Grandmaster in The Bronx. For simplicity’s sake, I’ll refer to him as Shock going forward.

Art by Gregory Jacobs, A.K.A. Rackadelic

According to Shock, “in New York you can’t really pay attention to the class without being picked on.,” and anyway, he had other things to focus on. So, within a couple of years, his grades tanked, and his mom decided to send him back to Tampa to live with his dad, who was more like that other show. He brought hip hop back with him, hooking up with a few other New York exiles to form The Master Blaster Crew, a group which he claimed was the region’s first introduction to the new genre. They started making some waves around Tampa, and Shock managed to channel that notoriety into a gig as an on-air personality on local R&B station WTMP, a job which he ultimately lost because he skipped a station identification break to play a 15-minute long Funkadelic song.

Shock on the keys

Around this time, when he was about 18, he took a step back from hip hop and started working obsessively to learn how to play the piano. He enrolled in the music program at Hillsborough Community College, and before long he was gigging regularly as a keyboardist in both funk and jazz groups around the Tampa area. Then, sometime around 1985, he and his then girlfriend, Davida, decided to drop out of college and move to Los Angeles, where he soon found work in a group called Onyx that played Minneapolis funk in the style of Prince, an artist who was second only to George Clinton in Shock’s pantheon of musical heroes.

It’s at this point that the story starts to get a little bit confusing. There’s very little information about the year or so that Shock spent in LA, except that he ended up quitting Onyx due to the dictatorial style of the group’s leader, who, according to Shock, "literally thought he was Prince.” At some point in there his relationship with Davida must have soured and, more significantly for our story, his passion for hip hop must have been rekindled. This might have had something to do with Ellis Kenrick Waters, known as Kenny K, the most mysterious character in the Digital Underground constellation.

Kenny K

Kenny K was also from Florida, where he hosted Tampa’s first hip hop radio show, The Kenny K Wax Attack, so it’s likely that their relationship dated from Jacobs’ time on the radio, but I can’t find any reference to how they met. One of the most confusing and contradictory things about this story is that he was supposedly hosting this show from 1986 until shortly before his untimely death in early 1994, exactly when all this Digital Underground stuff was happening on the other side of the country. It seems clear from this that his involvement in the group must have been severely limited, but I can only relate the information I’ve been able to find, so just keep in mind that there must be more to the story.

At any rate, Shock and Kenny must have reconnected during Shock’s time in LA, possibly when Shock was back in Florida for a visit, because within a year or so they were partners, calling themselves Spice Regime. At some point in 1986, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, they decided to make the move from LA to Oakland. It seems likely that this decision might initially have had something to do with one of Oakland’s greatest institutions, The Black Panther Party. According to Shock, “Me and my partner Kenny K were Stokely Carmichael fanatics.” Apparently they were more than just fans too, because Kenny was one of the pall bearers at BPP co-founder Huey P. Newton’s funeral in 1989, although what the story with that may have been is also not entirely clear.

Kenny K again, in the only photo I’ve been able to find from the Spice Regime period

Apparently the original idea of Spice Regime was for it to be a Black Panther themed hiphop crew, complete with berets and military fatigues. According to the story, just when they were getting that going, Public Enemy came along with a similar aesthetic and, according to Shock, “we were like, ‘Damn, they did that to the fullest, way better than we were even thinking about.’” What’s not clear is just how serious they were about the project. Shock mentioned him and Kenny having participated in a radio station “Battle of the Jams” together, but he also made several comments in interviews implying that he was feeling burnt out after his experience with Onyx and wasn’t interested in pursuing music as anything but a hobby.

What is clear is that Shock got a job in a local musical instrument shop, and there he soon encountered a customer named Jimi Dright, better known as Chopmaster J. It doesn’t seem like the two of them ever particularly liked each other. Shock described J as “just real status and material,” and J, in an interview with YouTube hip hop fanatic Soren Baker, compared their relationship to that of Keith Richards and Mick Jagger, who he said, “can connect and still get together and make money, but I don't know if they care for each other off the stage. Shock and I, we kind of have that relationship.” However they may have felt about one-another, J had three things that Shock didn’t have: money, connections, and ambition. If the two had never met, Digital Underground might still have been a thing, but it probably wouldn’t have been something that anyone outside of the Oakland underground hip-hop scene ever heard about.

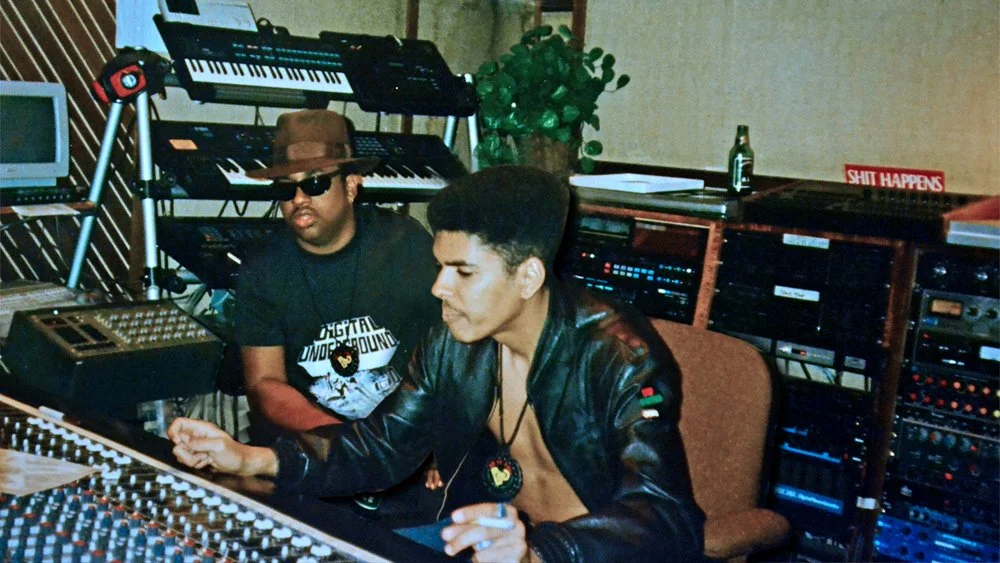

Chopmaster J and Shock in the studio

At the time when they met, Shock had been trying to use equipment in the shop to put songs together during his downtime, but he wasn’t happy with the progress he was making. Then in walks J, a jazz drummer who was looking to buy a bunch of recording equipment. According to Shock, he had lots of credit but very little idea of what to do with the stuff, so Shock, who seems to have always known how to do everything, sold him $5,000 worth of gear and offered to give him a few lessons on how to use it in exchange for access to make a couple of demos. They reached an agreement, and Shock recorded two songs at J’s new home studio. One of them, “Your Life’s a Cartoon,” which uses a sample from Henry Mancini’s “Pink Panther Theme,” is an example of Spice Regime’s BPP inspired polemical material, which Shock later referred to as “preachy and arrogant.” The other, “Underwater Rimes,” was likely inspired inspired by Kip Addotta’s “Wet Dream,” a non-hip hop spoken word record from a couple of years before that used a lot of similar word play, and “M.C. Space” by MC Shan, one of the few precedents that existed for fully fantasy-oriented hip hop, which also features a similar “computer woman” voice at the opening. With it’s light, comedic tone and sample of Parliament’s “Aqua Boogie (A Psychoalphadiscobeta-bioaquadoloop),” this was the track that clearly pointed in the direction where Shock was heading.

Kip Addotta and MC Shan

Much later, Shock would insist that he had only recorded these songs “to send to my little brother and hip-hoppers back East, not to enter in any contest or for the public.” As he explained, “I was fifteen years tired of that, and I’d started to believe my father [who felt that the idea of becoming a professional musician was unrealistic].” By this time, though, J was seeing dollar signs, and he wasn’t about to let Shock’s reluctance get in the way of his gravy train. Unbeknownst to Shock, he made a copy of the songs and started shopping them around to people he knew in the record business.

The first single

By the time he revealed all this, the damage was done. He made Shock an offer. He would get them a deal in exchange for membership in the group and a 50/50 split of all future profits. Shock, not seeing any reason to take J seriously, accepted the offer. Over the following months they experienced a couple of false starts that seemed to confirm Shock’s suspicions, but then, against all odds, J managed to come through with a small label called T.N.T. that had been started by an old friend from the Jazz scene, Rodney Franklin, and Atron Gregory, the tour manager for N.W.A.. Shock rerecorded “Underwater Rimes” and “Your Life’s a Cartoon,” and the songs were released as a 12” single on September 15, 1988.

Part 3 - Not Your Average Everyday Rap Crew

This is the point where it really makes sense to start talking about “Digital Underground,” although, in reality, it was still just Shock, with a few friends helping out here and there and J taking charge of the business side of things. The name was born slightly earlier, during one of the false starts I mentioned, when a representative from Tabu Records told Shock that the name “Spice Regime” just wasn’t cutting it, so he came up with a new one. In an extremely stoned interview a couple of years later, Shock explained what the name meant to him. "The Digital stands for the fact that we’re using digital equipment and that we’re taking R&B, black American music, to the next phase. You see? But the fact that it’s on the underground is the fact that you’ll never really know who the fuck we are. Everybody wants to know who’s in the underground. Is Humpty and Shock the same n****?…(waves hand dismissively) What we’re trying to show is that it don’t matter who’s who, or that WE get famous. It’s all about the music and the message we convey. OK? Don’t ever forget that!” In other words, the name Digital Underground represents Shock’s dream of taking the concept of George Clinton’s Parliament and Funkadelic, a large and nebulous collective of largely anonymous musicians embodying characters and putting aside individual glory for the sake of sheer theatrical spectacle, into the next generation.

Shock (center) with heroes George Clinton (left) and P-Funk drummer Gary “Mudbone” Cooper (right)

In the world of 1970s funk music, in which players were used to being semi-anonymous members of large bands, this idea was innovative, and maybe even a bit weird, but not exactly out of line with the tradition. In the intensely individualistic world of hip hop, in which relentless self-promotion is practically a given, it was considerably more revolutionary, although it also harkened back to the early days of the genre, when Shock was a teenager in New York and the scene was dominated by DJ-driven crews like The Fantastic Five, The Cold Crush Brothers, and The Funky Four Plus One, before Kurtis Blow showed up and introduced the concept of the solo star rapper, which has more or less dominated ever since.

Shock, who, in a video press kit for Sex Packets, described Digital Underground as “the all Atlantic, all pacific grand imperial dance music and hip hop dynasty… [with] members that are from all different geographic regions throughout the world,” had a slight tendency to exaggerate, and it’s not entirely clear whether the group ever quite lived up to his dream of what it could be. What is clear is that, in 1988, he was still basically just a guy with a regional underground hip hop single out, and once again, if it hadn’t been for the hustle of Chopmaster J, he might have stopped there.

With a record in hand, J started going out and hitting the radio stations hard, and he quickly started to make some inroads with local college and public stations like KALX and KPFA. Then, in a stroke of luck, one of the songs, probably “Underwater Rimes”, was featured on a segment called “Kiss it or diss it” on KMEL, a major commercial station. Of course, listeners kissed it, and this led to not only semi-regular play on the station but also opportunities to perform as an opener for big-name acts coming through the bay area.

In the end, the record sold around 20,000 copies, which was pretty good for an indie single. Then, a friend of J’s named Daria Kelly who worked in a local record store sent a copy to a friend in New York who was an intern at Tommy Boy Records. Tommy Boy, which had gotten its start with Afrika Bombaataa’s sci-fi tinged hit “Planet Rock,” was one of the dominant forces in the New York hip-hop scene at the time, and one of their newly signed acts, De La Soul, had a humorous sensibility and hippyish message that resonated with what Shock had been doing. According to J, it was members of De La Soul who heard the record and convinced Tommy Boy’s A&R guy, Dante Ross, to give Digital Underground a shot.

Tommy Boy’s iconic logo

This was a huge deal. It’s worth remembering that, despite the existence of Ice-T, whose Debut, Rhyme Pays came out in 1987, N.W.A., whose breakthrough album Straight Outta Compton would be released in January of 1989, and M.C. Hammer, who, I was surprised to learn, already had a double platinum album under his belt before Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em made him a household name in 1990, the west coast was still regarded as a hip hop backwater. As far as I’ve been able to tell, Digital Underground was the first west-coast hip-hop act to get a deal with an east-coast label, which is an indication of both how special what they were doing seemed to be and of how much the hip-hop scene was in flux at the end of the 80s. Tommy Boy gave them money to record a single and told them that if they could move 80,000 copies, they could make a full album.

Now Shock just needed two things, a new single and a crew. At this point, in addition to Chopmaster J, whose musical involvement seems to have been pretty minimal, the only other member was Kenny K, Shock’s DJ, who was apparently becoming too unreliable for live performances because of his responsibilities back in Tampa. As Shock put it, “Tommy Boy wanted to see a group, so I had to get one going! I always wanted Digital Underground to be this big supergroup, but we didn’t have all the true characters yet. Basically, most of the time if I had a vision of a kind of guy we needed, I’d just be that guy.” Most desperately, they needed a DJ, and they soon came across a teenager from Oakland named David Elliott, AKA DJ Fuze, who had been working with his childhood friend Ron Brooks, AKA Money B, in a group called Raw Fusion. It’s not 100% clear how this happened. In various interviews, Shock claimed to have met Fuze through a girlfriend of J’s and that they knew each other from performing at the same talent shows. Either way, they were impressed with what he could do, and, after coming in as a sub for Kenny K a few times, he agreed to join the group for a tour, on the condition that they also bring in Money B.

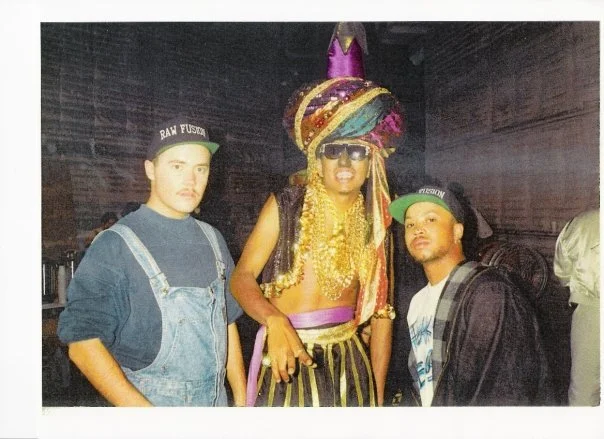

Raw Fusion: Money B and DJ Fuze

Unlike the eclectic Shock, Fuze and Money, both bay area natives, were dyed in the wool hip-hoppers. According to Money B, they were brought in as a duo, in part to give the group a more modern hip hop flavor, and never asked to choose between Raw Fusion and Digital Underground. In fact, Raw Fusion became the group’s standard opening act, and their signature, more street-oriented sound can be heard on a few DU releases. Later on, Shock helped them to secure a deal for themselves, and they released two albums with The Walt Disney Company’s short lived hip-hop label, Hollywood BASIC, but both Fuze and Money remained dedicated to Digital Underground and stuck with the group until it finally dissolved in 2008.

With the basic group now in place, Digital Underground went into the studio and recorded “Doowutchyalike”, a nine-minute long pure party track that serves as a slightly pervy manifesto for Digital Underground and their message of nonjudgemental freedom. In addition to their general philosophy of doing what you like, there are several other key elements of DU’s style that first make their presence felt in this song. First, it’s constructed out of a dizzying collection of samples, including three different songs by Parliament, one by George Clinton solo, one by Prince, one by KC and the Sunshine Band, and a vocal hook from Doug E. Fresh’s “Keep Risin’ to the Top,” among many others, while managing to sound relatively simple and straight-forward.

The Second Single

Second, although Shock had already introduced the characters of MC Blowfish, who takes the hilarious final verse of “Underwater Rimes,” and “The Computer Woman,” who I had never guessed was actually one of Shock’s alter-egos, as well as Rackadelic, who created original artwork for all DU releases, “Doowutchyalike” takes Shock’s character concept to a new level. The Computer Woman and Rackadelic are back, along with the introduction of Shock as the Piano Man, and an array of guest vocalists including local MCs Mac Mone, Bulldog, and Sleuth as well as Chopmaster J, identified as C.M.J., and most memorably, Shock’s younger sister, future fashion designer Elizabeth Carson Racker, playing the part of child rapper “Baby Dope.”

Baby Dope enjoys a soft drink (liner notes)

But what’s much more unusual is that a bunch of the rapping on “Doowutchyalike” occurs in a back and forth dialogue between the “normal” version of Shock and another Shock, doing a voice that was apparently originally intended as an impersonation of the distinctively British 80’s rap star Slick Rick. I haven’t found anything to confirm this, but I would guess that the voice originally related to the use of the hook from Doug E. Fresh, Rick’s partner from the Get Fresh Crew, but it started to take on a life of its own during the production of the single’s video.

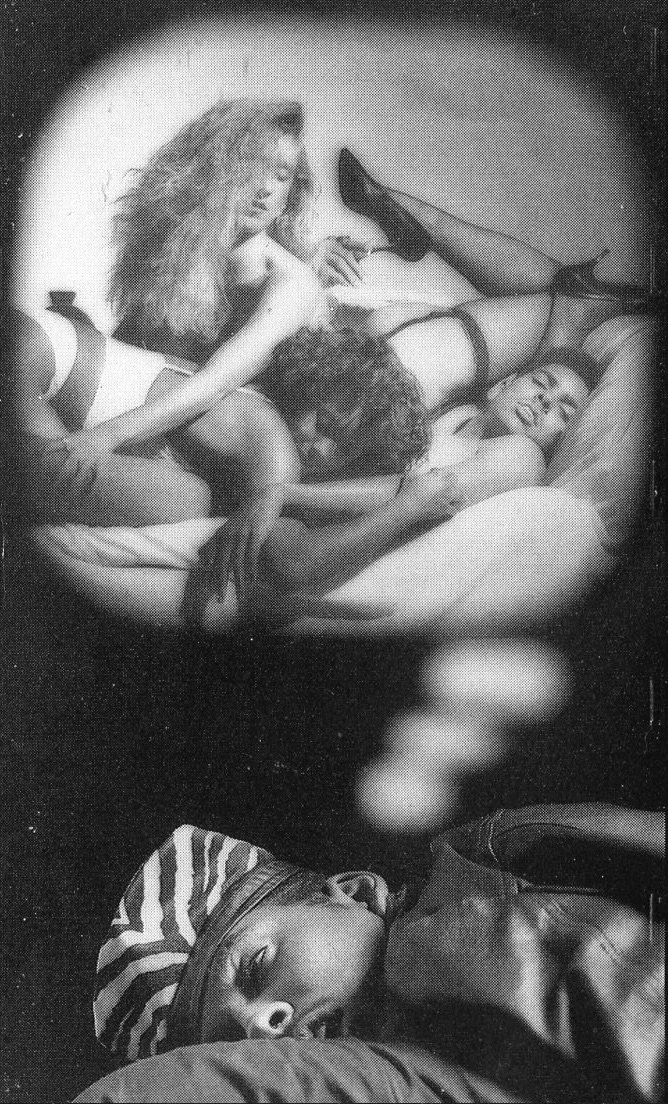

In order to promote their single, the group came up with the appropriate and relatively inexpensive solution of hosting a party at a local motel and filming it, along with some shots of the group performing and mouthing the words of the song as they walked around. The resulting music video steps up the perviness of the song considerably (although it’s still relatively mildly by the standards of the era’s rap videos, it should be said), but for the most part it serves as a charming and on-message introduction for the group and their signature aesthetic.

During their preparations for the shoot they visited a party store to stock up on supplies, and while they were there, in a moment of destiny, they came across some across some Groucho Marx glasses with African-American skin tone. Shock put them on, with the mustache removed, and it was immediately clear that they had found the look to go with Shock’s Slick Rick voice. The resulting character, who they named Humpty Hump, became the clear star of the video, and there was some kind of magic to him. As Shock would later say, “I really believe a lot of Humpty’s energy, soul, and sense of humor is in the outfit. It’s possessed. Try on a Groucho nose and glasses, a plaid suit, and a big fur hat and you’ll see what I mean. Then light a cigar and put on some hip-hop and it’ll pour right out of you. Try it one Halloween.”

Part 4: Old School, New School, R&B, or Hip Hop?

“Doowutchyalike” was an underground hit, helped along by its crossover appeal for fans of Electronic Dance Music, particularly in Europe. Within a few months it had sold 90,000 copies, and Digital Underground was given the green light to record a full album for Tommy Boy. The group descended on the home of their road manager, Neil Johnson (AKA Sleuth), and there they entered into an intense period of putting together material, with a festive atmosphere helped along by a combination of alcohol, cocaine, mushrooms, ecstasy, mescaline “yellow giggle drops,” and prodigious amounts of marijuana.

After an unspecified amount of time alternately partying and songwriting at Sleuth’s house, Shock and his growing crew entered Richmond, California’s Starlight Sound studio and efficiently recorded the album in two weeks, for around a third of the $60,000 advance they had received from Tommy Boy. Ultimately, including Underwater Rimes, which they rerecorded and considerably improved with a new beat, much less reverb, and a hook featuring Money B, and “Doowutchyalike”, which they kept as is, they put together fourteen songs and three brief musical interludes, which, for what I assume were practical reasons, they combined differently on the CD, LP, and cassette versions of the album.

There were also three songs that you could only hear on the cassette version, which is unfortunate, as they’re really three of the most interesting songs on the album. The first, “Hip Hop Doll,” which was the B-side to “Doowutchyalike,” is a straight-forward narrative about shock being so focused on trying to put the moves on a classy, east-coast hip-hop enthusiast in an Atlantic City casino that he doesn’t even notice when he wins $10,000 at the craps table. It’s particularly notable for containing Shock’s rendition of the song “Hello, Ma Baby” in the style of Michigan J. Frog, star of a classic Warner Bros. cartoon, which was, according to Shock, the original seed for what became his character, Humpty Hump (see below).

DJ Fuze, Shock G (Humpty Hump) and Money B, backstage

The other two cassette-only tracks were more anomalous. The first, the ironically titled “Sound of the Underground” is actually an example of the somewhat more hard-edged, stripped-down sound of Raw Fusion, the sub-crew consisting of DU’s youngest members, Money B and DJ Fuze, both of whom idolized Oakland’s DIY hip hop hero Too $hort. With it’s hard-hitting 808 beat and heavy rock guitar sample, from Queen’s “No More of that Jazz,” it immediately sets a tone that’s in stark contrast to the good time funk sound that predominates on the rest of the album, and for the most part, the contrast is refreshing. The song is only marred, in my opinion, by a metaphor in the final verse comparing Money B’s verbal domination of a hypothetical opponent to sexual assault, something that would have been tasteless in 1989, and certainly isn’t going to win Raw Fusion any new fans today, at least not any that they would like to have.

The early days: Busy Bee performs with a DJ, maybe Disco King Mario

The second, “A Tribute to the Early Days,” may be the closest thing to a recreation of a classic freestyle tape from the late 70s that exists in studio-recorded hip hop. Dedicated to Shock’s hip hop mentors from Queens, his cousins Gregory and Rene Negron (DJ Stretch), their friend Shawn Trone (MC Shah-T), and Shock’s favorite queens rapper, Shock-Dell, the song is produced to sound like it was recorded by someone in the audience with a hand-held tape recorder and performed over Kenny K spinning a stripped-down break-beat from “Put Your Music Where Your Mouth Is” by The Olympic Runners, a favorite song of Kool Herc’s original MC, Coke La Rock. Shock, along with Doc P, another partner from his days in Tampa, rap with the distinctive sing-song cadence of groups like The Cold Crush Brothers and The Funky Four plus One, employing standard old-school formulas like “Yes, yes, y’all, and you don’t stop, Ah keep on, ‘til the break of dawn,” and telling the story of Doc P’s encounter with an extra-terrestrial B-Boy and Shock’s with a “freak” who sneaks into his house to seduce him and tells him he has “a dick like a Whopper, but it tastes just like a Big Mac.”

Of the songs that actually made it onto the LP and CD releases, two, “The Way We Swing” and “Rhymin’ on the Funk” are elaborations on the basic theme of “Doowutchyalike.” The first, opening with Sleuth posing the classic question, “What’s up with the Underground, man, You guys old-school, new-school, R&B or hip hop?” seems to be an attempt to get ahead of the hate that they anticipated from the wider hip-hop community. As Money B put it, “At the time that the album came out, everybody was so tough and serious. Grab the mic, hold your dick, act hard. And we weren’t like that,” so shock makes it clear from the offset that following current hip-hop trends is not their objective, rapping “we don't play for other hip-hop crews, it's not about you, We do the things that we wanna do.” This song is also notable for containing an approved sample of Jimi Hendrix’s riff from the song “Who Knows.” According to Shock, the Hendrix estate was so notorious for rejecting every request that Tommy Boy initially didn’t even want to attempt it, but George Clinton, who just happened to be at the label office when the discussion happened, made a call and was able to secure the rights.

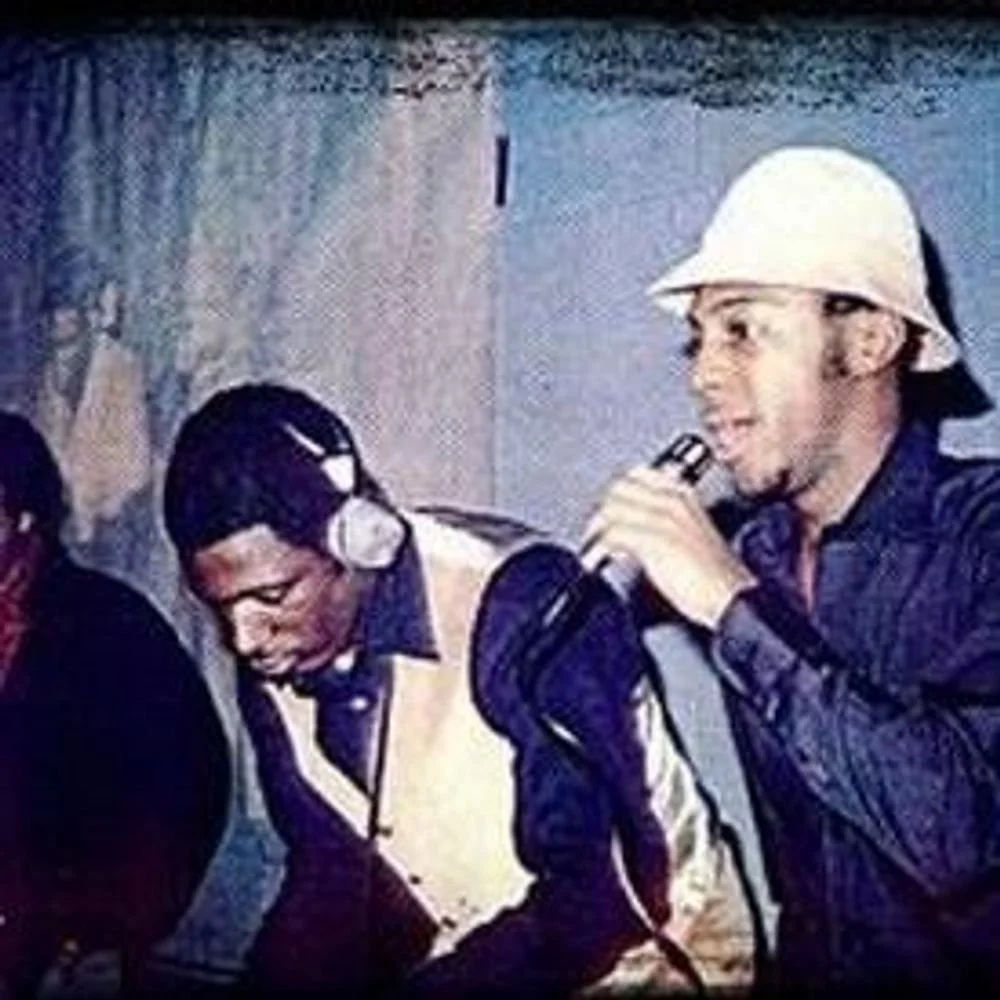

A fresh-faced Shock performs

“Rhymin’ on the Funk” is a song that celebrates DU’s connection to the P-Funk tradition, over a sample of “Flashlight,” Shock’s favorite Parliament song, while also paying homage to “Me, Myself, and I,” another song built around a parliament sample by DU’s closest kindred spirit on the hip-hop scene, De La Soul. Just for fun, Shock and Money decided to write verses for each other on this track, which gives it a slightly uncanny effect. This may also explain how Money B ended up recording the lines, “'Cause I know I'm the poop, Steaming hot, stinking up the dance floor.” It should be noted though, that immediately after, and presumably in exchange for this act of self-deprecation, Shock also gave Money a chance to shout out Raw Fusion, so I guess it all worked out for the best.

Somewhat less memorable, at least for me, are “The Danger Zone,” a straightforward and painfully earnest song about the crack epidemic, and “Gutfest ’89,” which basically amounts to a description of a music festival as imagined by someone whose entire experience of the entertainment industry is limited to strip clubs. The former seems like a return to the more serious, Black Panther Party inspired, vibe of Spice Regime, and the presence of a verse by Kenny K supports this interpretation. According to Shock, it was placed on the album to set the stage in case DU ever wanted to pursue this direction further in the future, an eventuality which, fortunately for everyone, doesn’t seem to have ever come to pass.

The latter has always been my least favorite song on Sex Packets, because it takes the objectification of women, something which pops up in several other songs on the album, and which sadly seems to have always been a blind spot for Shock, to a level beyond what I can really feel comfortable listening to. For that reason, until I started researching for this piece, I had almost always skipped it. Now, having forced myself to sit through it a few times, I do have to admit that it does contain one of the album’s best beats, sampling Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say” and some of it’s tightest rapping, especially from Money B, but I think I’ll still usually skip it.

The process of putting the album together also included a couple of serendipitous complications that helped to turn the album into the timeless classic that it ultimately became. The first involved “Freaks of the Industry,” the song with which my Sex Packets journey began. Originally, they recorded “Freaks…” over a sample of “Love Hangover” by Diana Ross, which is where the whole “if there’s a cure for this…” thing that they do near the end of song comes from. Ross, or her people, rejected their request to use the sample, which must have been frustrating at the time, but the Ross version of the song, while still pretty cool, is dramatically slower than the official version, and just doesn’t have the same magic.

Then they recorded another version using George Benson’s “This Masquerade,” but Benson, a Jehovah’s Witness, also refused to clear the sample. After that, according to Money B, in a last ditch effort to salvage the song, “we ran all over San Francisco to find that Donna Summer [“Love to Love You Baby”] to sample.” Thankfully, they secured a copy, and both its pace and its Moroderian clockwork sexuality turned out to be the key ingredients to bring out the full potential of this incredible song.

Part 5: Pronounced With an “Umpty”

The second was arguably even more significant, if not for me personally, then for the world. Apparently DU had recorded a song called “Underground System” using a sample from Kraftwerk’s “The Man Machine,” which sounds like it must have been pretty awesome but sadly Kraftwerk, possibly annoyed at the song’s use in 2 Live Crew’s “Dick Almighty” earlier that year, refused to clear the sample. This left the group with a gap in their track list, and they decided to fill it by developing Shock’s Humpty Hump character, who had already been making waves through his appearance in the “Doowutchyalike” video.

Although Humpty had started out as a more-or-less straight-forward impersonation of Slick Rick, which may itself have been influenced by Shock’s imitation of Michigan J. Frog (as heard in “Hip Hop Doll”), by this point he had evolved into his own thing. According to Shock, the myriad influences that went into the Humpty persona additionally included Bootsy Collins, Rodney Dangerfield, Morris Day, and of course Groucho Marx, but the main model was his uncle Tony, who he called, “a true-life Humpty without the nose.”

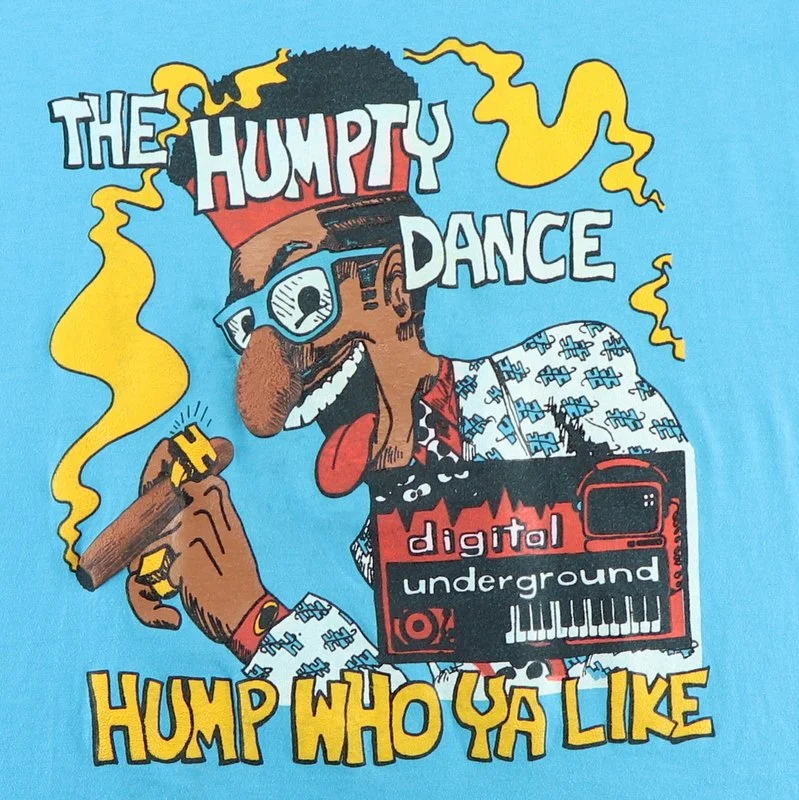

They quickly put together a song to give him a chance to introduce himself to his adoring public in all his bizarre grandeur. The result is, on the one hand, the closest thing to a conventional hip-hop song to be found on the record, but on the other, a spot-on perfect parody of the genre’s relentless self-promotional impulse, which is otherwise so conspicuously absent from Digital Underground’s work. As Shock put it, “The Humpty Dance” was a strange oasis on the album, because it’s the only time that anyone talked about themselves. That was outside the concept… …It’s an album that’s not conscious of self. It’s more about ideas than it is about us. Humpty could brag all he wanted because he was a cartoon character”

Humpty’s combination of awkward, off-putting nerdiness and irresistible self-confidence resonated with audiences, and it didn’t hurt that “The Humpty Dance” was one of the hottest party tracks on the album. The song is mostly built on a sample of Parliament’s “Let’s Play House,” which is where the “gimme the music,” and “Do me, baby” hook lines come from, but in the process of creating it, in what Chopmaster J has described as “a beautiful mistake,” they encountered a strange sequencer glitch that resulted in the uniquely swelling bass sound that Humpty imitates, “Err-rear, der-rit, err-rear, der-rit,” just before he describes his dance. This made the song unmistakable, even from a distance, and as the song developed into a hit, it became one of the signature sounds of the early 1990s.

The Third Single

They released “The Humpty Dance” as a single in January, 1990, two months before the whole album came out, along with a party video produced, on the model of “Doowutchyalike,” in the immediate aftermath of the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. According to numerous sources, the quake also directly influenced the creation of the dance itself. Shock, an easterner, had never experienced a big one before, and his panicked reaction when it started inspired a move that evoked, in his words, "bracing yourself ‘cause the ground is moving.”

They also went to considerable lengths to create the impression that Humpty Hump was a real person. They created a real name for him, Eddie Humphrey, and a bio, which Shock spread through press releases and radio interviews. Briefly, Eddie was a modestly successful lounge singer and fry cook in Tampa until a freak deep-fryer accident permanently altered his voice and severely scarred his nose. Understandably, this incident led him into a period of heavy drinking and depression, which only ended when his half brother, Shock, invited him to join Digital Underground, thereby unleashing his signature swagger and giving him a new reason to live.

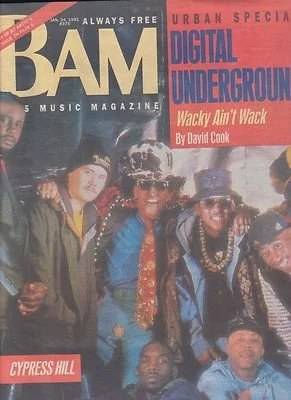

Oakland artist Michael Webster stands in for Humpty Hump on the cover of BAM (Bay Area Music) Magazine

In order to add verisimilitude to this fiction, they also employed body doubles, including Shock’s real brother Kent, a rock guitarist, to allow Shock and Humpty to be on stage and in promotional photos together, as can be seen in DU’s legendary performance in Dan Akroyd’s beautiful train wreck of a film, Nothing But Trouble(1991). The Video Press Kit that DU made for Sex Packets even features a scene of Humpty, in the studio, talking with Shock, in the booth. These efforts were surprisingly successful, and the true identity of Humpty Hump remained a point of controversy for years after. As far as I can gather, Shock didn’t officially cop to being Humpty until around 2004, when he released his first solo album “Fear of a Mixed Planet” and started to speak more openly about his character-building process.

Shock’s brother Kent. One of the Humpties.

“The Humpty Dance” was an immediate hit, reaching number 11 on the Billboard Hit 100 and number 1 on the US Rap Chart, which had just been created a few months before. Ultimately, it became one of the most iconic songs for people in my generation, at least in the US, which you could be almost guaranteed to hear at any party when I was in high school and college. This status was a major source of pride for Shock, who said in an interview nearly 30 years later, “That song is an American classic. It’s in Karaoke books!” But that’s not even where the legacy of “The Humpty Dance” ends!

If you’re reading this, it’s probably safe to assume that you know this song pretty well, but it’s likely that you’ve heard it a lot more than you ever suspected. It turns out that the unusually insistent drum track that DU created for the song, using a loop from Sly and the Family Stone’s “Sing a Simple Song” and a snare hit from Parlaiment’s “Theme from The Black Hole,” along with a few home-made elements, almost immediately struck a chord with producers looking for a new sound for the new decade.

Promotional photo for “We’re All in the Same Gang” featuring unknown Humpty Hump stand-in

Within a few months of its release, the beat appeared in “We’re All in the Same Gang,” a mega-collaboration of west-coast hip hop stars that was produced by Dr. Dre and featured him and his N.W.A. colleagues MC Ren and Eazy-E along with King Tee, Michel'le, Tone-Lōc, Above The Law, Ice-T, Young MC, MC Hammer, and Digital Underground, among others. From there it started to take on a life of its own, and by the end of 1990, elements of “The Humpty Dance” had appeared in at least 10 songs, including LL Cool J’s hit, “Mama Said Knock You Out” and two Ice Cube songs, “Jackin’ for Beats” and “Who’s the Mack?”

Over the next few years, the beat would pop up in “Return of the Mack” by Mark Morrison, “If U Can’t Dance,” by the Spice Girls, both “Jump” and “Warm It Up,” By Kris Kross, “Live and Learn,” by Joe Public, “His Story,” by TLC, and many more. All told, WhoSampled.com lists 184 songs that sample “The Humpty Dance,” which doesn’t quite put it in the top tier of the most sampled songs, but it was certainly enough to make it a ubiquitous part of the soundtrack of an era. A few years later DU even recorded a track, “The Humpty Dance Awards” to poke fun at producers for their over-use of their creation.

Shock takes a packet (from the album liner notes)

Part 6: Biochemically Compacted Sexual Affection

This is all great, you may be thinking, but what about sex packets?! Well, I’ve been saving that for last. It all starts with Shock’s some-time roommate and party partner, Earl Cook, AKA Schmoovy Schmoov (sometimes spelled Shmoovy Shmoov). Schmoov was a high-voiced R&B singer with a fantastic voice, which Shock compared to Curtis Mayfield, but he had just scored a good job as a Project engineer for MCI, and he apparently wasn’t that much into hip hop, so he was never more than a peripheral member of Digital Underground. He was, however, a kindred spirit for Shock, who shared his passion for P-Funk and Prince, and who may have even had him beat in terms of eccentricity.

Schmoovy Schmoov - the mind behind Sex Packets

In his free time, Shmoov had been working on a concept for a new drug, which he called Genetic Suppression Release Antidote (GSRA), affectionately referred to as sex packets. The basic concept of sex packets is perfectly and succinctly explained by Shock, as the packet man in the song “Packet Man”:

“It's like a pill, you can either chew it up

Or like an alka-seltzer, dissolve it in a cup

And get this: see the girl on the cover?

You black out, and she becomes your lover”

Sample packets created by DU

According to Shock, this was actually something that Shmoov was serious about developing as a real product. As Shock explained, “Shmoov really believed he was going to get a grant from the United States government to develop this technology to help astronauts have sex when they traveled. I thought it was a brilliant idea, but I didn’t think technology [had] reached a point to where we could induce a dream and allow someone to see who they wanted and have sex with them. Acid and ecstasy were close, but it wasn’t quite that.”

Shock saw this idea for what it really was, the perfect extension of the Afro-Futuristic narrative concepts of the Parliament-Funkadelic “Funkology” into the late 1980s, an era plagued by the terrifying dual epidemics of AIDS and crack cocaine. Together, Shock and Shmoov started to develop a song, an epic 7 and 1/2 minute slow jam over a dramatically slowed down sample of Prince’s banger “She’s Always in my Hair.” The result, “Sex Packets,” is an exploration of the sex packet concept from several different angles.

Schmoov and Shock sing “Sex Packets” (Video Press Kit)

It begins with Shock, in the role of the Packet Man, providing a basic pitch, “Sex packets, a dollar or two, Just tell me, how many for you, This time… This time,” followed by a straightforward description of the product, “Now it's just sex in a pill, It gives me such a thrill, it's nice, And it's a guy for a girl, or a girl for a guy, Try one tonight.” This leads to a brief narrative about a character, also Shock, who is unconcerned about his partner not being in the mood, because, as he says, “no more will I ever have to Jack it, ‘cause instead, I can just take a packet.”

From there, we get a glimpse inside the actual packet experience, which turns out to be surprisingly conversation heavy, as Shock instructs his packet partner (also Shock, in his “Computer Woman” guise) to “hold it like this,” “Just put it in your mouth,” and even, “Just hold me." Then, overcome with passion, Shock exclaims, “It feels so real,” to which the computer woman responds, with an unquestionably ominous sensuality, “It IS real.”

Shock’s packet experience (liner notes)

All this is punctuated by increasingly intense repetitions of a sort of motto: “No sex can be safer, it’s a pill, wrapped in a little piece of paper.” As the song nears its climax, and perhaps as Shock’s character begins to lose touch with the distinction between reality and packet-fueled fantasy, another voice, this one a smooth, soulful falsetto, enters, singing the lines, “I'ma give ya what ya heart, I’m just givin’ to your love, And I'm feelin what you need, Uncontested ecstasy!” (Or something like that)

There’s more that I could mention, including a brief introspective moment with the packet man, who laments “I just sell them, I cannot do this love,… this love,” and a spectacularly percussive piece of R&B back-up vocals when all the vocalists on the song come together to ecstatically exclaim “SEX PACKETS!” But there’s no way to touch on every delightful detail, so you really just need to give it a listen.

The accumulation of all this is an overwhelming and immersive tribute to the sex packet experience, and just like “Freaks of the Industry,” it’s all done with a completely straight face, in what may be the ultimate statement of Shock G’s Rowan Atkinson-level ability to be hilarious while acting like he had no idea he was being funny.

Naturally, the people at Tommy Boy were thrilled with the song, and, based on some statistics that they’d seen, showing that, according to Shock, “the word sex attracts the eye 10 times more in records stores,” they suggested that Sex Packets would make a great name for the whole album. This was probably what Shock and co. were hoping for anyway, and now, with the blessing of their label, they started to go all in on the concept.

Shock’s depiction of the Packet Man

To reinforce the spookily electro-chemical vibe of “Sex Packets”, and to make the song feel more like a central event rather than just another song on the album, they created a thick, reverby piano laden instrumental “Packet Prelude” and “Packet Reprise,” both featuring the computer woman’s creepily titillating motto, “It IS real.” Then they created another full packet-oriented song, “Packet Man” this one presenting a straight-forward narrative of a drug deal with the now time tested combination of Shock as Shock and Shock as Humpty, now in full comedic dialogue mode a la Abbott and Costello.

Much as they did with Humpty, Digital Underground also made considerable efforts to generate ambiguity around the question of whether Packets were truth or fiction. Shock and Shmoov read up on the toxicology of hallucinogens to get the proper lingo and created an official looking pamphlet, which they then distributed in hospitals, bus stations, etc., asking the question, “Sex Packets: A true alternative to safe sex in HIV times, or a dangerous street drug?”

The best image I’ve been able to find of the packet pamphlet

They also started to speak publicly about packets as though they were a real thing. As Shock told a local radio host in June 1989, “Sex packets is the theory. It’s something that we discovered that was going on, they were developing these packets for astronauts during space travel. They say, you know, scientists say, that men are more productive when they’re sexually satisfied or whatever, and sometimes they’re in space travel for a long time, so just like food packets, they were developing these sex packets, which kinda leaked out and became a small street epidemic in some places.” Exactly how seriously all this was taken isn’t 100% clear, but the idea apparently gained enough traction that NASA at one point issued an official statement denying of the existence of packets, which probably did more than anything else to convince people that they were real.

All of this paint’s a pretty dark picture that was perfectly attuned to the anxieties of its time. The basic narrative seems to be that the fear of AIDS drives people to turn to packets as a safer alternative to human sexual contact, only to find themselves reduced to crack-like level of servile addiction. The fact that Packets are a secret product developed by the US government doesn’t hurt the story either. The video press kit even features clips of “packet addicts,” their faces darkened to protect their identities, along with a brief interview with the “inventor” of Sex Packets, “Dr.” Edward Earl Cooke, who bluntly acknowledges that his creation has inadvertently led to a street epidemic.

Dr. Edward Earl Cool, AKA Schmoovy Schmoov

Interestingly though, this bleak scenario is almost completely absent from the actual album, which seems to deliver a quite different, and almost purely celebratory, message about sex packets. Even in the album’s only mention of the G.S.R.A. backstory, a dedication to “Dr.” Cook, hidden away at the end of a massive “Thank Yous” section in the liner notes, there’s no hint of a darker side to the story. The only obvious exceptions to this are the ominously knowing voice of the Computer Woman, who’s clearly up to no good, and one brief sketch featuring a packet enthusiast who, having offered up a brand new TV and VCR for barter, has the packet man suggest a trade of packets against actual sex with the his actual human wife. The sketch is, of course, played for laughs, but the implications are pretty clear.

Of course, this stark contrast could simply be the result of the album’s party vibe, which might not have benefitted from too much discussion of drug-addled dystopia, but there is another possibility that I find intriguing. Curiously, Shock G frequently spoke about the sex packets concept as something that applies to the whole album, not just to the sex packets “suite” that ends it. He might just have meant that the entire album has a preoccupation with sex that isn’t necessarily characteristic of DU in general.

Parliament album art by Overton Lloyd

That’s at least part of the story, but it occurs to me that, in the “Funkology” narratives that Shock adored, there are always heroes, like Doctor Funkenstein and Starchild, who take action to shield intergalactic society from the forces that threaten it, mainly unfunkiness. In Sex Packets we clearly have a force with the potential to have a devastating effect on society. Perhaps Digital Underground themselves, with their doowutchyalike ethos and pervy predilections, are the heroes, offering an unapologetically fleshy and undeniably human alternative to the dark road of “biochemically compacted sexual affection.” If this were true, it would mean that Shock, nearly fifteen years after having his original hip-hop name shot down by his cousin, had finally truly taken his place as the (MC) Starchild of a new and glorious Funkology.

Digital Underground riding high around Summer 1990, with unknown Humpty Hump stand-in. Notice Tupac Shakur, who joined the DU circle shortly after the release of Sex Packets, peeking over the top.

Epilogue: Yo, World, I Hope You’re Ready for Me

With the album completed, Digital Underground immediately headed off for their first tour of Europe. Before they left, each of them had to ask their bosses if they could have their day jobs back when they returned. Up to that point, none of them had been able to make enough money from their music to support themselves, and there was no reason to anticipate that changing in the near future. While they were away, on what was by all accounts a successful tour, they knew that “The Humpty Dance” would be released on January 20, 1990, but they had very little idea of what else was going on back in the States. When they returned to New York, they were shocked to have people recognizing them in the airport, and to hear their song blasting out of car windows throughout the city.

“The Humpty Dance” took about 8 weeks to go platinum. By that time the album itself had come out and sold 500,000 copies in the first two weeks, ultimately rising to number 24 on the Billboard 200 (album chart) and to number 8 on their Top RnB/Hip-hop Albums Chart. It would be certified platinum on September 18, 1990, two years and three days after the original release of “Underwater Rimes.” This was the beginning of a heady period for Shock and his group, which included tours with Public Enemy, LL Cool J, and Queen Latifah, among others, the stewardship of Tupac Shakur, who they would hire as a roadie in the Spring of 1990, and, to be sure, lots of extremely wild parties.

They never did quite get back to the level they rose to in 1990. Ironically, it was the wave of west-coast 70s funk based hip hop that they started, which ultimately became their undoing. The Dr. Dre-led cavalcade of “G-Funk” Gangsta Rap that flooded the airwaves of the early ‘90s, while based on the basic model DU had developed, left their good-time party vibe looking quaint and old-fashioned by comparison.

Nonetheless, they kept going and released five more albums, two EPs, and a greatest hits compilation, and they continued touring until Shock finally decided he’d had enough in 2008. Even today, almost exactly 35 years after it was released, Sex Packets is still reaching new audiences and offering a touchstone to free-thinking people of all ages and backgrounds, showing us all that it’s ok to be ourselves, even if that sometimes means getting stupid, and do what we like.

So, on behalf of all of us freaks, I’ll close by saying thank you to Shock, Money, Fuze, Kenny, Shmoov, and also to Chopmaster J. Without you guys, the world would be a darker and much more boring place.

-Peter Lawson

Altered greeting card (RSVP cards, artist believed to be Sarah Burns) from Shock’s memorial service. According to KQED in San Francisco, the modification was done by Shock himself before he passed.